Haleakala: The Fast Way

*Photos: Eddie Gianelloni

-->

Haleakala: The Fast Way

“Mainland, yea?”

Biting the top of her knuckle, the old wooden desk creaking as she

leaned in heavy. Pressing the

phone to her ear and tripoding her elbows on the desk, she listened close for a

few more seconds then looked up at me and asks: “So the dogs came after you?”

her tanned forehead crinkling into the shape of a ‘V’.

“Well, no. Not

really.” Pausing mid sentence and

putting myself in the ranchers boots on the other end of the phone line; this

must sound ridiculous. A runner

from the mainland with no shirt and short shorts wanders off his ranch into the

Kaupo General Store and wants to know why his dogs, specially trained to

protect the livestock, come after him when he runs towards the livestock.

Meg presses the old phone back to her ear then leans back in

her springy office chair: “Okay, thanks John, got it.” I wander aimlessly in the cubical sized

store. Meg tilts her head,

pinching the phone to her shoulder and shouts, “Just don’t try and steal any

goats and the dogs won’t bite you.”

Loud enough for the neighbors to hear it.

Leaving camp early that morning with the plan of running

from the Kaupo General Store, at sea level, to the top of Haleakala, a ten

thousand foot volcano on the island of Maui, things had not gone as

planned. With livestock spread

across the route at three thousand feet and big white dogs ready to protect,

retreating to find out if they bark or bite was the only option.

I’d met a lot of interesting people since pedaling out of

the open air baggage claim in Kahalui.

An Olympic caliber runner and sometimes artist living upcountry on three

hundred acres of ranch land, he chases down goats, oddly enough, on long runs

from his door and sells them on Craigslist to get by; a group of long hairs

that’d turned grey as they watched the world change and develop around their

tent-beach community; and a Dutch man training full time to become a

professional iron distance triathlete who’s never raced an iron distance

triathlon—he’s strong, it’ll probably happen. The people you meet from the saddle of a bicycle or pair of

trail shoes defines the journey.

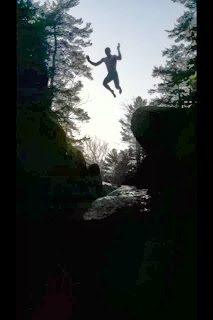

Going after three big human powered objectives unsupported and solo, the

trail, ocean, and open roads bring great solitude and clarity. It starts like any good adventure—with

strong microbrew and detailed topo-maps.

With a couple pairs of running shoes, a bicycle and Bob

Trailer loaded down with camping gear and three pounds of quinoa, collectively

known as Tuktuk, I bought the cheapest airfare I could find. On a budget of twenty dollars per day I

aimed to (1) set the fastest known time (FKT) trail running from sea level up

ten thousand vertical feet to the summit of Haleakala Volcano; (2) ride Tuktuk

around the one hundred and sixty mile circumnavigation of Maui faster than

anyone has ever recorded; (3) swim across the nine mile Auau Channel from Lanai

to Maui. The bike ride was long

and arduous and the swim was too windy and crossed a whale migration path

during whale migration. This is a

story about running from the tropical waters of the Pacific, through jungle,

ranch land, tree line and to the top of Haleakala’s moon-like crater.

10:00 AM December 14,

2012:

I’m tired and the dogs look angry. Quickly scrambling to the bottom branches of an old tree, I

could see the double track winding through two big knolls dotted with goats—seemingly

aesthetic until I heard the barking.

Climbing steeply to four thousand three hundred feet in the first three

and a half miles after an hour and a half ride to the trailhead from camp; the

clock was ticking and I was tired.

Perched and sweating from the humidity, all I could think about was

stories from Colorado: “…if you are in the high country and come across a group

of sheep with big white Burmese-mountain-type dogs, turn, and run like hell in

the opposite direction.” Unfortunately

I’m like a kid touching a hot burner for the first time—it’s not real until you

experience it firsthand.

Retreating back to the Kaupo General Store my effort was

thwarted. The first section was

hard enough, navigating head-high jungle grass through a maze of wild pig

trails, looking for tree trunk colored sign posts with small white arrows. There is no established trail until

four thousand seven hundred feet, where a person goes through a chain link

fence that signifies the Haleakala National Park boundary. The lower half is pure cross country on

Kaupo Ranch land. The rancher

opened the route as a courtesy to hikers, but let it be known he is still

ranching and has dogs trained to protect the livestock from predators or the

like. Back at camp I fell asleep

dehydrated and over trained—for the past two weeks I’d been riding Tuktuk from

trailhead to trailhead loaded down with all her gear. If I was going to complete the route I needed a different

approach.

Breaking the budget and renting a car for a day, I set up base

camp at Hosmer Grove near seven thousand feet on the other side of the

crater. Figuring the most

efficient way to do the run would be duel sport; lock the bike to a fence post

at the summit, watch the sunrise, drive around to the opposite side of the

island where the trail starts, run the route, and ride fifty miles back to the

car into the setting sun.

7:00 AM December 17,

2012:

No matter where you start, 10,000 feet is still

ten-thousand-feet. A marshmallow

of weather squished the summit on run day. Forty mile per hour gusts, sideways rain, and less than

twenty feet visibility left me grinding my teeth with crossed arms in an overcrowded

visitor center. The summit parking

lot was an ant hill of tourists from sea level who’d come from eighty degree

weather in Kihei wearing tank tops and flip flops; there was frost on the

ground. The three mornings prior

had been a blue-bird sunrise with a full moon and bright stars fading to calm

weather and views of adjacent islands.

Frustrating, but today was not the day—I extended the rental car and

drank overpriced coffee in beach cafés.

4:30 AM December 18,

2012:

The stars are close enough to touch from the door of my

tent; recovered and anxious, it’s time to run. What took ninety minutes on recon took forty. Moving quickly but conserving energy, I

met two Peruvian guys who tend to the goats. We talked in Spanglish for a couple minutes, I told them

about my first encounter with their dogs, now sitting obediently five feet away

and ready to work. I nick named

the dogs Pica and Rico. The

Peruvians offered me a ride on their four wheeler, I gave them a high five, and

ran up the hill.

Steep double track with bowling ball lava rocks slow

progress, but soon gives way to more gentle fell style running across wind

exposed fields with long range views of the Kaupo Gap; the long ramp exiting

the crater through sheer walls and leading down to the ocean. Knee high sub alpine grass-land and

eucalypt forests defines the middle section of the run. The route sees little traffic below the

crater—if there ever was a proper trail the jungle ate it a long time ago. Around five thousand eight hundred feet

a pristine alpine trail emerges and it’s time to hammer. Climbing nearly six thousand feet in

the first five miles, steepness backs off, the wind dies down, and the crater

walls close in protecting the runner from weather systems crashing into the West

side of the volcano.

Low hanging cloud bands hover around three story cinder

cones and the trail gives way to a lifeless moon-like sand box. I’m thankful for the moisture in the

morning air making the sand play dough.

The sun aluminates the stacked ridge lines of red, orange, and brown

lava rock. The route hugs the left

wall through the belly of the crater via Sliding Sands Trail. This upper section is one of the most

unique alpine runs a person will ever

experience.

The final three thousand feet is dry, on deep sand, climbing

sustained switchbacks, and it hurts.

From the bottom of the crater I start to push hard toward the distant

ridge—what I thought was the finish line.

Six miles and three thousand vertical feet later the number of tourists

multiplies and I reach my bike.

Eighteen miles, ten thousand vertical feet, three hours and thirty seven

minutes made for one of the most dynamic and varied runs I have ever done.

Unlocking my bike a grin spreads across my face—I was about

to coast down ten thousand feet of brand new road as the sun set. As luck would have it, my pedal broke

at mile thirty and it starts to rain just as the road turns to dirt and

cobblestone.

Comments