The Golden Mean: Searching for the perfect Distance

It’s the rhythm of breathing fresh air deep into my lungs as I work up a hill and the sound of my feet as I float down its back. The open space and restorative solitude, no telephone poles or cement—just two valley walls cradling a river and a trail. It’s getting up before the sun and starting the day with endorphins and inspiration; I run in the mountains because it is free.

I’ve never considered myself a runner. I’m not built like runners in the magazines and jogging was always a means of punishment in organized sports growing up. Late to practice? Four laps. Lost the game? Plan on extra running tomorrow. I also went through a long period of adaptation where I had to convince my large frame that it too could learn to be efficient. It all stems from a desire to gain insight from challenge. My career began on a Friday night after my best friend and his dad, both marathoners, invited me out for one of their ‘tempo’ days the next morning. Mid way through the ten miler my body gave up—I’ve been fascinated by the simplicity and challenge of going long ever since. I don’t think anyone’s perfect distance can be prescribed but you know it when you’re there; the mind and body pump life through your arteries in unison and the rest of the world becomes irrelevant.

***

Nate and I first met in Halong Bay Vietnam, near the China border. He was on Cat Ba Island to climb the limestone pimples jutting from the water; I had just ridden my bicycle from Burma and needed somewhere to sort my thoughts. We were both confused and fresh out of University, taunting a nine to five from the other side of world. After running in the jungle and crashing a moped twice, we made plans to meet in the Cascade Mountains for a traverse of the Stuart Range. In mid August the following summer, Nate finished teaching his last outdoor education class in Yosemite and drove north.

***

“It’s not a question of whether or not we’re off route, rather, how off route are we.”

I heave and flop to meet Nate on the ledge and respond by peering off in the direction he’s been leading out, there’s nothing but a thermal draft pushing up a thousand feet of shelved rock. The crevassed glaciers look like dry cheese being forced to bend.

The first look over the escarpment, even if one is accustomed to the vertigo of mountains, is shocking. In a nanosecond the eyes gauge the fantastic drop, the mind imagines the plummet to death, instinct secrets a warning into the blood and the body recoils.

Turning my back to the wind and facing the wall I begin stemming out off the ledge, my right leg wanding out into space before landing on a fridge size boulder. The whole block teetering as I weight it. Looking forward to re-establish on a fixed point I catch a glimpse of Nate, already out of ear shot and buzzing up the ridge. Neither of us are moving quickly but my ego is dwindling and I can tell he wants to keep pushing.

***

It made perfect sense when I learned both Nate’s parents are doctors, he loves to problem solve. When we met he was carrying around a rebuilt circa 1970s point and shoot camera with slide film. He’d snap a photo, put on a pair of wire frame spectacles and eventually announce the picture had in fact been captured after tinkering around for awhile. His backpack looked well traveled with cuts and scrapes from mountains all over the world, with a couple home-made patches holding on the sun faded shoulder straps.

I took all this as a good sign. The older the gear, the better. People with new gear scare me: the scanty wear-and-tear of their equipage is too often indicative of the scantiness of their experience, which means you don’t want to go on a hike with them, let alone traverse an entire range together.

Other long distance junkies I’d met before our traverse had a propensity for self improvement, which I can relate to. There always seemed to be some deep seeded dissatisfaction becoming more transparent as they would tire. Ironically, the more lost and worked we were the happier Nate got; it drove me nuts. Some innate ability would keep him from losing composure and, more importantly, the connection with his body’s limits. His pacing technique a micro chasm of his healthy training philosophy; work within yourself and listen closely to your body’s feedback.

One good measure of an adventurer is how he acts when he is uncomfortable. Does he whine, keep quiet, or revel? The former is unforgivable, the second acceptable, the last admirable.

***

Finally catching my breath and balance on the rock I scream in frustration:

“Stop moving God damn you!” I laugh a bit as Nate turns, surprised he can still hear me. He doesn’t respond, just motions to come meet him on the high point of the ridge.

The landscape ahead undulates, getting tighter and tighter constricting from the width a small house down to the size of a sidewalk. Beyond Nate is a vertical stair case of granite leading up to what looks like the summit block. The running and scrambling isn’t technical but the exposure off either side would bite back. Steep boulder fields on one side and a sheer drop on the other—take your pick. Most of the granite is shelved and makes for easy ascending but backtracking feels like a slip and slide covered in Crisco.

I reach Nate and immediately notice his sunken eyes from dehydration. We both look at each other and laugh; I must look just as bad. We’ve been above a water source for a couple hours and still have a long section until we drop off to the Teanaway River Valley on the south side—saving my cheeky remarks about his orienteering skills I say nothing and take the lead.

My footwork feels weak and powerless, fatigue working from my core out to my limbs. I’m out of sync and lumbering to keep pace, my mind drifts back to the last time I felt this deprived.

***

I drove up to Penticton, British Columbia, missed the race briefing and slept in the back of my car as close to the race start as possible. I didn’t have disk wheels or a carbon bike and fueled most of the race on Snickers Bars, but I knew the distances and how they felt. In the months leading up to the event I would see the finish line with my eyes closed before falling asleep; imagine the toll of ninety degree temperatures during the marathon on chilly morning runs and simulate the feeling of crossing the finish line with a smile after swimming a couple miles, biking a century and running a marathon.

Three miles from done at Ironman Canada I drifted back to the strong finishes I imagined, the early mornings I’d sacrificed for lonely open water swims and started to repeat my training mantra—“Rhythm and Speed.” I crossed the line happy and embraced the long awaited experience. An hour or two later I crawled back in my rig with a gallon of water and three pieces of pizza—the race was just as I’d imagined, but with 3,000 extra people.

***

Reaching the high point of the traverse with Canada still fresh on my mind and lagging synapses, we were met by a clap of thunder and the priceless question anyone who has ever laced up a pair of running shoes can relate to—ought we turn back? It doesn’t matter how long the run is, eventually there comes a time when you either turn in hopes of getting home quicker by retracing your steps or press on into the unknown and risk things getting worse.

It’s that moment of regret; a run that starts smooth and fast, runner’s high just setting in, birds chirping, sun on your back, then a huge bug flies into your eyeball. Or you’re out on the easy loop in your neighborhood and need to go number two, no bathroom in sight, half way to home with a friendly looking lady waving from her garden; you do everything you can to look normal. Regardless of the distance, eventually there comes a time when elements beyond your control call for judgment.

Turning to see sheets of rain stained pink from the sunset marching in with flashes of lightning. We’re at nine thousand feet, fifteen hours from the car and need to make a decision, quick. This is the first time I’ve seen Nate with a confused look on his face.

***

We were on the trial by 4:30am after a parking lot bivouac, getting the tail-end of the stars as we started running. Leaving a car on the south side the previous day, the idea was to do a single push and the plan was to keep moving. The trail left the gravel parking lot seven miles up from Icicle Creek, and the access road out. After rolling along the valley floor next to Mountaineers Creek for a couple hours we reached a marsh and our first glimpse of the Stuart Range.

Mt. Stuart is the centerfold for the central Cascades. Every year thousands of outdoor enthusiasts from the city parade into the range, permit in hand, and spend three or four days breaking in the trails through alpine plateaus and meadows; by late August the trails are in perfect running condition. Two hanging glaciers pronounce the north ridge, eighteen pitches of stair cased granite. From the apex a craggy east flank reaches out with two more summits before reaching into the alpine plateau of the Enchantments, a pristine assortment of alpine lakes, streams and rock towers.

Before running smack into the base of the mountain the terrain is carpeted in second growth furs and pines with shawls of moss covering the granite lumps, turning to scree fields then crack and shelve systems up the wall.

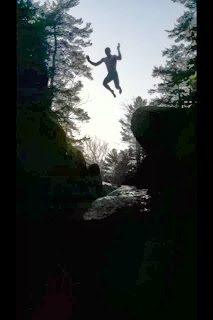

Something primal turned on when we ducked off trail. We’d run the equivalent of a half marathon and a couple thousand feet of gain on coffee and whisky burps from the night before. By the time we were leaping over small creeks and ducking under fallen trees I was high—everything around me stopped and the only thoughts were “Go. Faster.”

I imagine I’m chasing or being chased by a bigger animal; I picture myself in a strong and efficient body. When I find this meditation in races I don’t focus on other competitors or challenging terrain, just working within myself to move as fast and relaxed as possible. Time goes away, synapses fire and endorphins pour—it’s more intoxicating than any drug on earth.

***

“What do you think?” I ask.

“I think it’s going to rain then get dark and cold.” Nate responds plainly. Now shivering on the summit block.

“Descend and retrace or push to the car?” I ask knowing he’s already decided.

“Probably have more fun looking for the trail in the dark.” He chirps while shouldering his pack.

Following the cairns (rock-piles to mark the trail) from the high point on the ridge, we descend like a tornado down the Cascadian Coular. Arms flailing and feet sliding, we hit the Teanaway Valley floor to the south yearning to be back on trail while we can still see it. The rain had caught us and a sheet of dark was starting to pull over the west rib.

Within twenty minutes we intersected the trail paralleling the range, tension immediately lifting. I started to stomp puddles and lead a fast pace in the final couple miles to the car thinking about an old fashioned milk shake and my hammock; I felt like a kid again. The distance was perfect—there had been doubt, discomfort and flow. Though it is not to say that all runs and races need to be forced epics, a bit of adventure and crisis reminds me how fun running can be.

It wasn’t until I loosened my grip on forcing out mileage and starring at my heart-rate monitor that truly began to enjoy the miles. Running became more meditative when I drew awareness to my body’s feedback; some days I need twenty miles in the mountains, other days all I want is three around the neighborhood. In an over prescribed culture, take some of the tension off your mind by listening to your body.

Comments